Buddhiman and I hop in a minibus back to Kalimati in Lamjung, cross the creaky bridge and walk through the now harvested rice fields to his home in Pipal Tari. Neighboring farmers ride their plows on the backs of water buffalo as others wave straw platters at the rice piles, blowing the chaff away. Everyone is friendly, a welcome respite after the unending touts in Thamel. At night the stars are vast above the open fields, with thousands of crickets chirp in unison and the occasional rhythm of a distant madal drum.

It's nice to have another few days off from the grime and hustle of Kathmandu. I've left Tara and Danny in the good hands of Monga. Between Danny's ears and Monga's computer knowledge, they should be able to keep the recording sessions running smoothly.

We came back for a Puja, a religious ceremony that Buddhiman's wife was going to hold. But she consulted a Brahmin priest who advised her to wait until December. In any case, we're here with camera and mic, and we spend the next day climbing up the ridge again to Moria (which means Banana tree by the way), and further along the ridge to a small shrine to Shiva, where Buddhiman plays a few tunes before clouds engulf the mountains to the north.

Buddhiman's son has joined us, and he picks up chesnuts for us along the walk. With Buddhiman in Kathmandu most of the time, Suman is mature for a 15 year old, hooking up the electicity in his house with simple wires and bartering for rice with the neighbors when Buddhiman's sarangi sales in Kathmandu aren't enough. I give him the sound kit to run for awhile and we film and record a passing donkey caravan and some local villagers doing odd farm chores.

Suman will probably never go village to village like the previous generation. Buddhiman's made enough for him to stay in school so far, and he'll be done in a year or two. After that his prospects are most likely getting married and going to Kathmandu to sell sarangis to indifferent tourists. But in any case, he's 15 and enjoying the cd player Tara and Danny gave to his father. He plays the rough mix of a song Buddhiman sings on nonstop.

We walk back beneath the ridge, passing round mudbrick huts, bamboo groves, and a small snake on the side of the trail. It's no bigger than an earthworm but Buddhiman holds us back. Really poisonous apparently.

"Do you ever see cobras down in Pipal Tari?" I ask.

"Sometimes."

"How big do they get?"

He holds his hands up to indicate the girth; about the size of a grapefruit. Then he tells me about how down in Chitwan, some snakes will latch on the the breasts of sleeping mothers to suck their milk. He says it's not uncommon for new mothers to die in their sleep from suckling cobras.

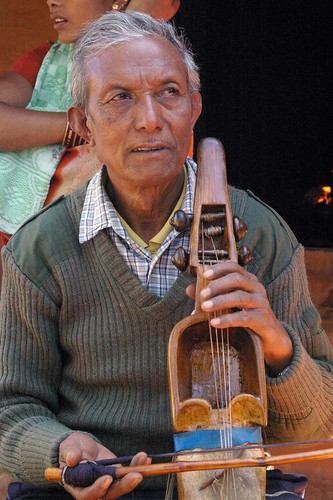

We cross the ridge and I ask Buddhiman to play a tune while the light's still good. He plays this

song (video from the cheap camera operated with my third hand--others busy recording sound, running the DV camera, and shushing loud passersby). The song is about Sagarmatha, better known to you and me as Mt. Everest. It's hard to tell how old some of the songs are. An old song can mean 5 years old to a Gandharba, as if there's no way to distinguish between the recent and distant past. And the Gandharbas are so used to improvising that a "new" song might just mean the one they just made up. Not the easiest stuff to document, but the melodies are often passed down, if not the words.

Back in the village we sit on Buddhiman's porch drinking raksi and eating dahl baht. Buddhiman tells me about how his father and grandfather were known to play songs to bring the rain. The rain would last the duration of the song. This skill has been lost, but was witnessed within living memory of some Gandharbas, like the ones we met in at Manoj's home in Chitwan. There was apparently a book containing the words to these rain songs in the Gandharba language, but this text was supposedly stolen by a Nepali and sold to an unknown foreigner.

Buddhiman plays a few more songs and we sleep, catching a bus the next morning back to Kathmandu. There's an accident on the road and we walk the last few miles into the valley,

catching a ride on top of an overcrowded bus.

That evening Monga, Dan, and I discuss cultural preservation and what we're really doing to encourage it among the Gandharbas. There's no way we could stop younger Gandharbas from listening to Hip Hop or wanting to move to the city to become street hustlers with miniature sarangis as tourist trinkets. Radio and television, which have replaced the Gandharbas as the storytellers in most rural villages, are not going away anytime soon.

Sure, we've donated recording equipment and helped some children go to school, but I think if we have any real impact, it will be on the kids of the elder Gandharbas we recorded, the ones who noticed someone else was interested in Grandpa's old sarangi, collecting dust on the wall. Maybe a few of those kids might ask for a lesson. But we'll never know.